The Ambassador Bridge connects Detroit and Windsor – image by cmh2315fl via flickr

Patrick Cooper-McCann and Andrew Guinn, Assistant Professors of Urban Studies and Planning at Wayne State University

Nearly 150 researchers and students are currently affiliated with the DePOT project. Historians and sociologists abound. Yet there are only a few scholars trained in planning or geography.

As urban planning scholars based in Detroit—specializing in community development and economic development respectively—we have affiliated with the DePOT project because studying deindustrialization challenges us to reconsider one of the foundational relationships structuring the built environment: the linkage between jobs and communities. Specifically, deindustrialization draws our attention to the decisive role that industry has long played in creating—and subsequently remaking—neighborhoods, cities, and metropolitan areas.

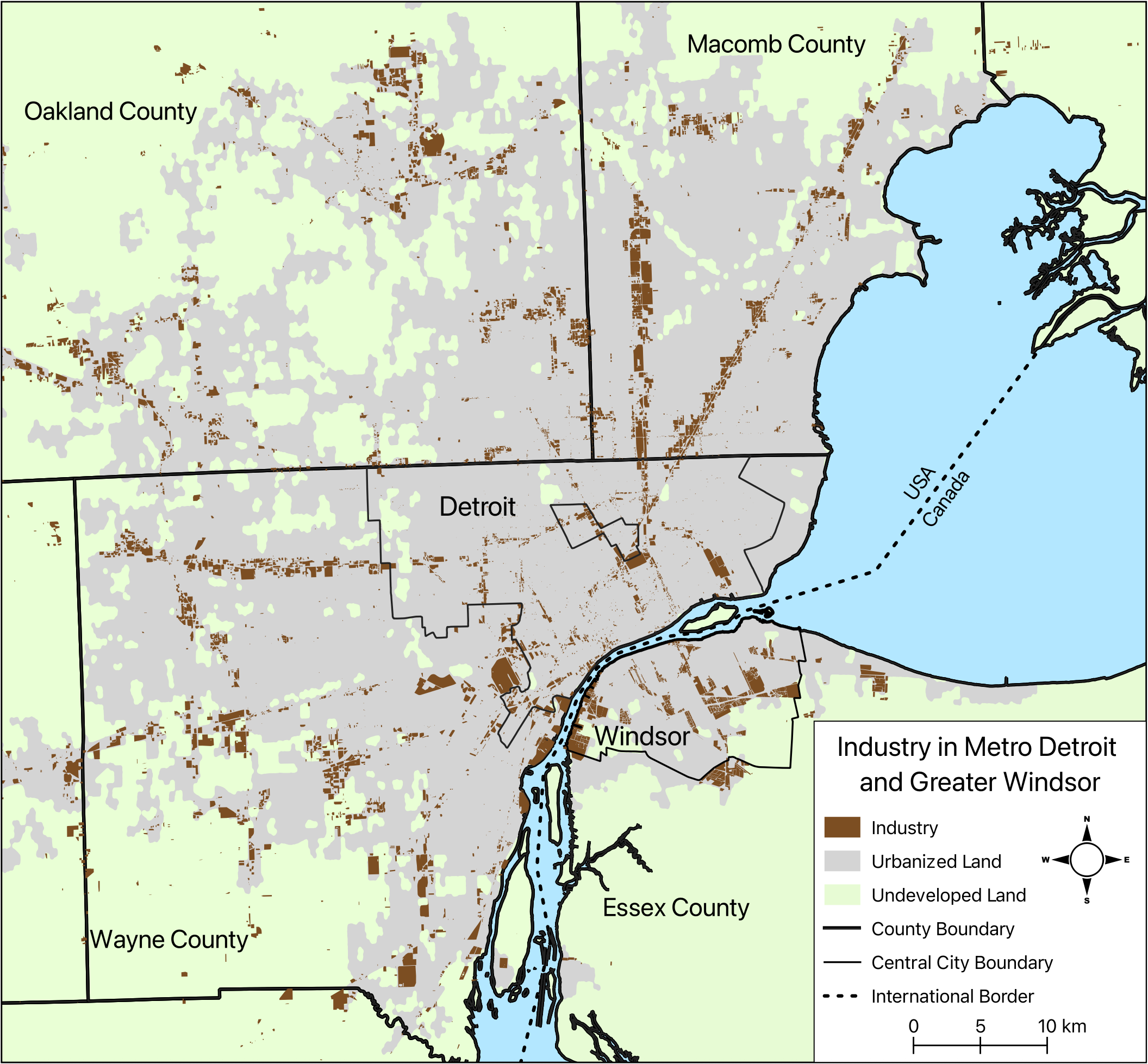

To better understand deindustrialization, we began tracing the growth and decline of every industrial district in the international Detroit-Windsor region from the late 1800s onward. This historical-geographical approach allows us to see variation within each of the two metropolitan areas that we are studying, not just between the central cities and their suburbs but also among the many industrial districts and corridors that crisscross each metropolitan area. The fact that Detroit and Windsor are border cities also enables us to compare policy responses across multiple scales, including at the city, metro/regional, state/provincial, and federal levels. Given the status of Detroit and Windsor as the “automotive capitals” of the United States and Canada respectively, we have devoted special attention to the auto industry, but we have studied other historically important industries as well, from stove making to pharmaceuticals.

What are we finding thus far?

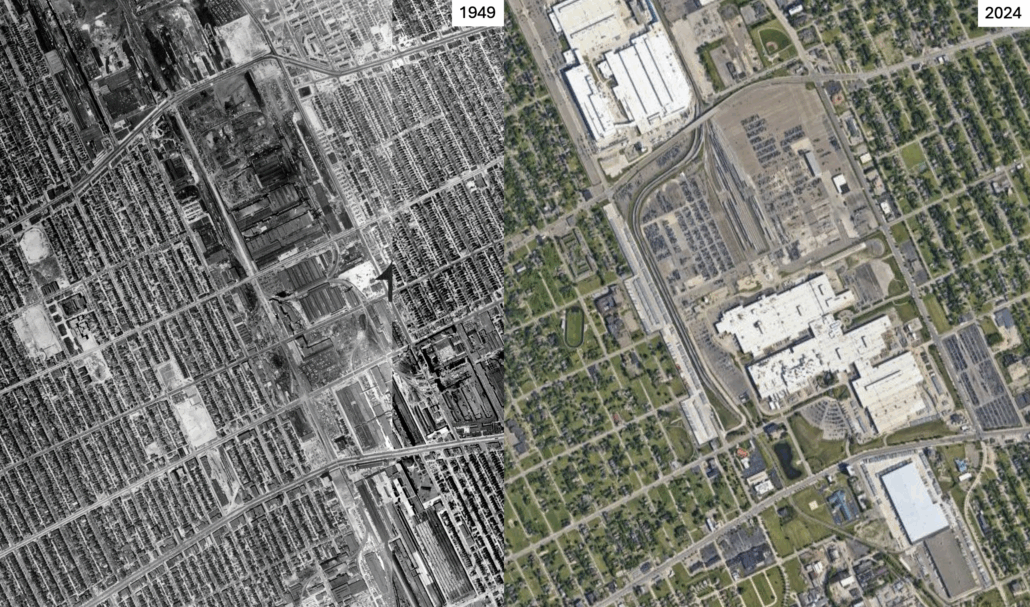

Once a diversified industrial corridor, the Greater Conner district is now dominated by the Stellantis Detroit Assembly Complex, and the district’s population has plummeted. Source: Wayne State University’s DTE Aerial Photo Collection and Google Maps.

First, Detroit’s oldest industrial districts began declining decades earlier than commonly recognized. Most research on Detroit correctly notes that manufacturing jobs began declining citywide in the 1950s. But the industrial areas bordering the central business district—which supported industries like cigar making, shipbuilding, and stove making in nineteenth-century buildings—reached their peak employment levels by World War I, after which factories slowly gave way to warehouses, parking lots, and abandonment. The next wave of industrial districts—those, like Milwaukee Junction and Highland Park, that fostered the early auto industry—already began shedding jobs by the mid-1920s. The neighborhoods around these districts peaked in population by the 1930s and led the city’s demographic shrinkage across subsequent decades. We attribute the decline of these districts to the relocation of firms to more modern facilities, together with the waning of some industries as firms contended with declining product demand, changing technology, competition with firms in other regions, and the effects of mergers, which became increasingly common after the rise of national finance capital.

Second, the timing, degree, and effects of deindustrialization vary widely both between and within Metro Detroit and Greater Windsor. In Metro Detroit, industrial growth has occurred in tandem with decline since World War I, with new industrial corridors growing at the expense of older ones. Michigan’s adoption of a “home rule” framework for local governance in the early 1900s encouraged local administrative fragmentation and inter-jurisdictional competition for investments. This has facilitated the outward spread of factories to suburbs where land is cheap and taxes are low, with older factory districts suffering disinvestment. Conversely, Canadian administrative traditions promoted the amalgamation of localities and imposed some limitations on sprawl. This has promoted the recirculation of people and capital in and around Windsor’s older neighborhoods and industrial districts—mitigating the spatial impacts of business cycles.

Greater Windsor’s auto industry has also outperformed Metro Detroit’s since the 1960s. Since the merger of the U.S. and Canadian automotive markets in 1965, both cities have competed with each other for investment, primarily from the Big Three and their suppliers. During each transition in the business cycle, these firms decide where to develop, shutter, relocate, integrate, or outsource production. Because the Big Three have been losing market share since the 1960s, Windsor and Detroit have been competing for a decreasing slice of the overall pie. Detroit and Windsor have also faced growing competition from locations in the U.S. South, Mexico, and overseas. Yet despite facing the same market conditions, Windsor has fared better economically because its factor costs are somewhat lower and its workforce is better trained, and because Ontario and Canada have repeatedly intervened to secure automotive investments for the city. Windsor has also fared better fiscally than Detroit because the city has been able to expand in size to capture the tax base from factories built on greenfields. These factors show that national, subnational, and regional/local policies have all played roles in mediating the history of deindustrialization and shaping its variegated North American geography.

Third, as we argue in a forthcoming article in Economic Development Quarterly, industrial reinvestment does not function like deindustrialization-in-reverse. Industrial districts no longer anchor residential neighborhoods in the manner they once did. Automation has reduced headcounts in factories, and every factory is now surrounded by parking lots, so industrial corridors support far fewer jobs per acre than in the past. Furthermore, many industrial workers now live far from where they work. Households living next to factories usually have no connection to manufacturing, besides enduring the associated air pollution, noise, and truck traffic. As a result, while investment in advanced manufacturing facilities remains crucial for bolstering regional labor markets and local tax bases, reinvestment in older industrial districts can actually hinder neighborhood revitalization, as has been the case with the repeated expansion of Stellantis’s massive Detroit Assembly Complex on the city’s east side. On the other hand, if pollution is held in check, public and philanthropic investment in homes, schools, parks, streetscapes, storefronts, and social services can spur neighborhood revitalization, even in neighborhoods, like Windsor’s historic Ford City district, that are hemmed in by factories.

Studying these cases reminds us, too, that despite many decades of deindustrialization, industry nevertheless remains pervasive throughout Metro Detroit and Greater Windsor, including in districts that peaked in employment a century ago. Understanding industry’s evolving relationship to communities is therefore a critical task for researchers of all kinds.