Drawing for a textile produced by Orinoka Mills – Courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt Collection

Yuan Yi is an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University in Montreal, Quebec.

–

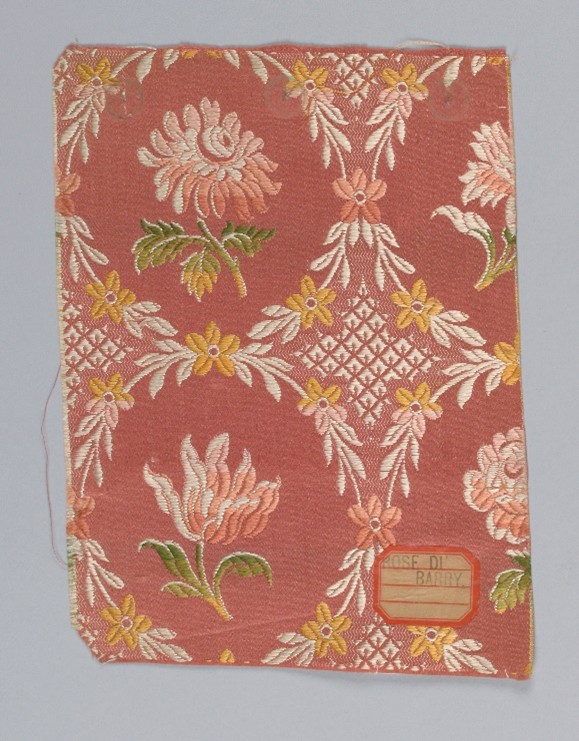

The Orinoka Mills started operations in the 1880s in the neighborhood of Kensington, Philadelphia. The company originally manufactured silk upholstery and curtain materials but abandoned the latter by 1898 to specialize in furniture covering. Its manufacturing capacity more than tripled in less than two decades from 85 looms in 1898 to 300 looms in 1913, all specializing in the production of silk, wool, worsted, and cotton upholstery.[1] A sample of Orinoka fabric made around 1910 allows a glimpse into the material culture of American households, cafes, and hotels in the early twentieth century, to which Orinoka and other American weaving mills made an important contribution (Figure 1). In the 1930s, the company made a strategic decision to move its weaving facilities to York, Pennsylvania and the American South, although its administrative offices remained in Kensington. Decades later in the 1980s, it once again relocated manufacturing facilities, but this time as part of its merger with Langenthal, a Swiss company that would be renamed to Lantal.[2]

Figure 1. A sample of fabric manufactured by Orinoka Mills, ca. 1910. https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18690795/

The relocation and eventual closure of the Orinoka Mills was not irrelevant to multiple waves of deindustrialization that swept through the American textile industry in the long twentieth century, both at regional and national levels: the deindustrialization of the Northeast and the simultaneous industrialization of the South and other suburban areas, and the eventual decline of the entire industry that started in the 1950s and intensified in the 1970s. Although Lantal is a Swiss company, the merger happened at a crucial moment when the U.S. was outsourcing manufacturing to “developing” countries, notably the People’s Republic of China.[3] The consequence was a familiar story. The workers of Orinoka, mostly power loom operators, lost jobs while their skill suddenly became obsolete. The fate of their looms was not that different. If they were still valued, it was because of the utility of iron rather than the complicated mechanisms inscribed in them.

One of their powers looms escaped the fate of scrapping and ended up on the shop floor of Rabbit Goody’s Thistle Hill Weaving, located in upstate New York (Figure 2). Goody started her career as a hand weaver but soon realized the limits of traditional handlooms as well as her body. She began to purchase used power looms from mills that were going out business and founded Thistle Hill Weaving in 1989 to produce historic textiles and custom fabrics. Today, after 35 years of business, her shop floor is packed with equipment that dates back to the 1890s and as recent as the 1960s. Her “old” machines still work great, perfectly serving her purpose.[4]

Figure 2. Crompton & Knowles power loom on the shop floor of Thistle Hill Weavers. Originally from the Orinoka Mills, York, PA, circa 1890. Photography by Yuan Yi.

All of Goody’s power looms were manufactured by Crompton & Knowles Loom Works, including the one acquired from Orinoka. A renowned weaving machinery manufacturer, the history of Crompton & Knowles is as long as that of Orinoka. Founded in 1897 by the consolidation of the Crompton Loom Works with the Knowles Loom Works, its main factories in Worcester, Massachusetts and Providence, Rhode Island produced over 200 different types of looms for weaving fabrics made of cotton, wool, silk, linen, rayon, and other fibers.[5] The company indeed formed a crucial chapter of early American industrialization featuring mechanized textile production—from the mass production of cotton fabrics in New England and the American South to the production of specialty goods in Philadelphia and elsewhere.[6] It also exported weaving equipment to global markets. As of 1931, its power looms were going to China, Japan, Canada, France, Italy, Belgium, Mexico, among others, while it continued to equip American weaving mills, including Orinoka.[7]

Neither Crompton & Knowles nor Orinoka exists today, which is part of the greater transformation: The U.S. is no longer a major manufacturing country of textiles or weaving looms. The decades-old Crompton & Knowles looms still in operation on Goody’s shop floor are certainly an anomaly that does not fit into this paradigm.[8] They also differ from other surviving power looms that ended up in a museum, like the one in Figure 3. Unlike this industrial heritage, which remains but never functions, thus squarely fitting into conventionally narratives of deindustrialization, Goody’s machines continue to perform their original task in an era of deindustrialization: to make fabrics. What does this anomaly tell us as we strive to figure out new directions for the field of deindustrialization studies?

Figure 3. Crompton & Knowles 1929 model used to produce prototype seating upholstery for Model Ts. From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company. https://www.thehenryford.org/artifact/352269/.

Goody’s business is far from mainstream—Goody and her team make small-batch, custom fabrics for a niche (somewhat luxury) market whose clientele is mostly comprised of museums, film industries, textile designers, and architects. Yet, their work is not entirely isolated from recent political and social movements, although Goody started her business well in advance of these developments. On the one hand, the U.S. has strived to reindustrialize its manufacturing sector—“a rare point of agreement” between the current and previous governments.[9] On the other hand, there has been growing global interest in reuse, repair, maintenance, and sustainability.[10] Despite their varying motivations and goals, all they challenge a general understanding of the linear progress from preindustrial to industrialization and to deindustrialization.

Goody’s “archaic” looms serve as a powerful primary source that complicates this familiar narrative. She works with “outdated” machines, but they are not “traditional” hand looms. She works with power looms that purportedly deskilled hand weavers, but her work requires much handwork and flexibility. Many believe that textile production has been deindustrialized in the U.S., but her team is still making all sorts of new fabrics by modifying, repairing, and repurposing decades-old machines, challenging our fundamental assumption about old and new. All this work requires skill and knowledge. When the Orinoka Mills closed, the industry lost not only their workers but also their collective skillsets. Goody and her team in a way have become “intangible cultural heritage” preserving the twentieth-century weaving technology—a combination of machines and the operators’ skill.

Will this anomaly form a new paradigm, especially after the “environmental turn”? We never know the answer before we have a full picture of all other anomalies from across the world that involve the use of “old” technologies. After all, not many anticipated that Orinoka’s power loom, the remnant of the industrial age, would live a new, productive life after the end of that era.

====

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Rabbit Goody for all our inspirational conversations.

Use of AI: I used Google AI to collect online sources and then verified and analyzed the most relevant ones.

[1] “Orinoka Mills,” Workshop of the World-Philadelphia, https://workshopoftheworld.com/kensington/orinoka.html.

[2] “Orinoka Mills.”

[3] Elizabeth O’Brien Ingleson offers a captivating revisionist account of this history in Made in China: When US-China Interests Converged to Transform Global Trade (Harvard University Press, 2024).

[4] “About Rabbit Goody,” Thistle Hill Weavers, accessed September 24, 2025, https://thistlehillweavers.com/rabbit-goody/.

[5] Andersen Meyer & Company, Charles John Ferguson, and Guangzhao Li, Andersen, Meyer & Company, Limited, of China; Its History: Its Organization Today (Kelly and Walsh, 1931), 168.

[6] On the difference between the two sectors, see Philip Scranton, Proprietary Capitalism: The Textile Manufacture at Philadelphia, 1800-1885 (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[7] Andersen Meyer & Company, Its History, 168.

[8] The anomaly-paradigm analogy is taken from Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (The University of Chicago Press, 1962).

[9] Farah Stockman, “Two Days Inside the Movement to ‘Reindustrialize,’ and Rearm, America,” New York Times, July 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/20/us/manufacturing-tech-trump-reindustrialize.html.

[10] See The Maintainers, for instance. https://themaintainers.org/.