Port Glasgow is a small town in the local authority of Inverclyde in the West of Scotland. For several centuries, this small corner of the world was globally renowned for its shipbuilding prowess. The PS Comet – thought to be Europe’s first successful commercial steam vessel – was built and launched in the town in 1812. Over a century later, the revered British artist Sir Stanley Spencer was commissioned by the War Artists Advisory Committee to capture the pivotal contribution of Clyde shipbuilding to the British war effort, painting seven triptychs and one singular piece, depicting different types of workers at Lithgows’ Kingston Yard in the town in 1940. For Spencer, shipbuilding was portrayed as a “religious act” (Jack 2022).

After a year’s fieldwork in Port Glasgow for my MSc – looking to spatialise the visual cultures of what Alice Mah (2012) calls ‘industrial ruination’ in the town – I found that the religious connotations did not stop there. The iconography of shipbuilding was ubiquitous in Port Glasgow, more so than any Christian symbolism. It was a town filled with memorials to its industrial history – so many in fact, that an entire map was created just so that people could find them. Some are placed prominently within the urban landscape, such as John McKenna’s Soviet-esque ‘Shipbuilders of Port Glasgow’ sculpture, colloquially known as the ‘Skelpies’, or Malcolm Robertson’s nearby ‘Endeavour’ sculpture of the bow of a ship. These memorials are hard to miss; others are more hidden. You have to wander and drift through the town to discover them, sometimes by accident. They may be sculptures and statues, commemorative plaques and plinths, or murals of all shapes and sizes. Some you may sit on, others you can walk right over without noticing – as I did. This vast array of visual cultures of memory is profoundly striking.

Equally striking however, are the spatial dynamics of this postindustrial town. Car parks, drive-throughs, motorways that cut directly through the centre of the town, vacant and derelict plots of land, fenced off and enclosed public spaces, shops boarded up. John Wood Street is one of the main roads in the town, sloping down from the train station into the centre, named after John Wood and Company, who moved their shipyard from nearby Greenock to Port Glasgow’s ‘East Yard’ in 1810 and built the aforementioned PS Comet there two years later. Almost all of the shops are ‘Common Good’ properties, meaning that they were “gifted to the Port Glasgow burgh many years ago by the shipbuilder Lithgows for the good of the local community” (Watson 2025). More than a third of these nineteen shops are vacant and boarded up.

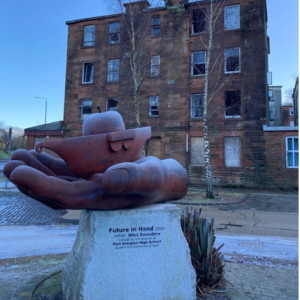

A short walk takes you to the large, colourful ‘Bay Street Murals’, depicting nine local shops painted onto the garage walls below a large post-war housing estate. These murals – themselves a form of memorialisation – conjure a strange emotional response. Why are there vibrant paintings of non-existent shopfronts only five minutes away from a main road filled with actually-existing vacant shops? Are these paintings a cruel reminder of what has been lost, or a call to action? Another ten minutes down the road, and we come across the Clune Park Estate – known in the media as ‘Scotland’s Chernobyl’ – as seen in the picture above. This was a large public housing complex made up of over 400 flats, built by Lithgows shipbuilding company at the beginning of the 20th century to house its workers and their families. These were the workers depicted in Spencer’s art, the artist having stayed on the estate during his time working in the town. Like much of the urban landscape of Port Glasgow, the fate of this housing estate mirrored the demise of shipbuilding from the 1970s onwards.

The deindustrialisation of this area led to vast job losses, and a sustained, decades-long depopulation of the area has followed. A report from September 2025 by the local authority reflected on these numbers: Inverclyde has lost approximately 22,000 people since 1981. Between 1998 and 2021, its population declined by 8.9% – the highest negative change for any local authority in Scotland. If the current pattern continues, it is projected to lose a further 6.1% by 2028, and another 13% by 2040. The Clune Park Estate was one such place that experienced this loss of people, having been largely abandoned since the start of the millennium, but only now in the early stages of demolition. When I visited the town, the place was naturally a ghost town – hence the nickname. Signage for a Covid-19 vaccine centre still hung on the fence around the local church, now a pile of rubble. This was a site in which a ‘polycrisis’ had unfolded over many decades.

One particular set of memorials to industrial history in this town left me with a salient, sinking feeling. Whilst searching for a sculpture dedicated to Sir Stanely Spencer, I initially walked along Argyle Parade with my eyes ahead, taking in my surroundings. Only on my way back did I look down at my feet. Etched into the floor of this walkway past a McDonald’s drive-through to a Tesco Extra the size of an aircraft hangar, are the names of five shipyards that no longer exist: ‘Newark’, ‘Glen’, ‘East’, ‘Castle’ and ‘Bay’. Walking across them had a haunting impact on the experience of wandering in the town. Not only did they go unnoticed by me the first time I walked over them, but their location is a fitting reminder of just how monumental the palimpsestic processes of deindustrialisation have been on the physical environment of this town.

Memorials are pieces of the urban landscape that allow for a “dialogue between past and present”, and thus their meaning is “never fixed” (Purcell 2003: 57). In Port Glasgow, this dialogue can only be centred around the losses that deindustrialisation has inflicted here – with only a vast array of memorials left to commemorate and remember. Linkon’s (2018) theory of the ‘half-life’ of deindustrialisation is palpable here, as depopulation, ruination and neglect have left an entire area vying for an as-yet-immaterial future. If the current predicted trends continue, the town will be waiting for that future for many years to come.

References

Inverclyde Council (2025) Repopulation Strategy 2025-2028. A Report by the Interim Director for Regeneration, 16 September 2025. Available at: https://www.inverclyde.gov.uk/meetings/documents/19511/10%20-%20Repopulation%20Strategy%202025-2028.pdf

Linkon, S. L. (2018) The Half-Life of Deindustrialisation: Working-Class Writing About Economic Restructuring. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Mah, A. (2012) Industrial Ruination, Community and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Purcell, S. J. (2003) ‘Commemoration, Public Art, and the Changing Meaning of the Bunker Hill Monument’, The Public Historian, 25(2), pp. 55-71.

Watson, C. (2025) ‘‘Most dismal town’ award scrapped after Port Glasgow backlash’, BBC News [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/clyql9vvv4xo