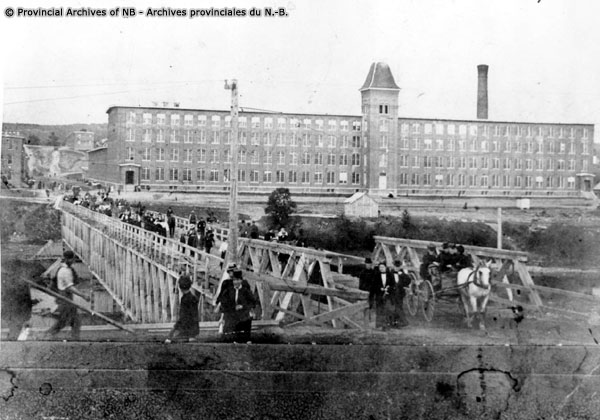

Marysville Cotton Mill – 1885, courtesy of the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick Reference number: P87-12

Noah Schwarz is a graduating undergraduate student in history and political science at the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton. This coming September, he will begin an MA in Political Science at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. This piece is based on research projects conducted for the courses HIST 3305: Deindustrialization in North America and HIST 5308: The Practice of Oral History, both instructed by Dr. Fred Burrill.

Marysville: Industrial Hamlet to Heritage District

Just a stone’s throw from the University of New Brunswick’s Fredericton campus is Marysville, a small, enclaved neighbourhood nestled on the banks of the Nashwaak River. Marysville, once an independent community dominated by textile manufacturing and now an amalgamated area of the province’s capital, is distinct from the rest of the city; the streets are lined with rows of identical brick houses initially built for the mill’s employees, all arranged around the community’s staple—the Marysville mill building.

Enticed by the national policy, New Brunswick industrialist and railroad baron Alexander “Boss” Gibson ordered the construction of the mill building, along with the town itself. Opening in 1885, the mill operated unstably, under various owners, until 1975 when the final owner, Whittaker Textiles, cited a combination of problems, including soft markets, high raw material costs, declining prices for finished products and foreign competition as the culprits for its demise.

The final closure of the mill left the newly amalgamated community without a primary industry and, as Alex Forbes argues, brought about “the most vulnerable period in Marysville.”[1] Along with the loss of the mill’s jobs, the neighbourhood dealt with deteriorating facilities and sidewalks, a lack of city services, low police protection and a host of broken amalgamation promises from the city of Fredericton.

Amid this period of vulnerability, the question of what would be done with the mill building lingered. As one of my interview participants explained, “people wondered what would happen to it [the mill], just sitting there for years and years.”[2] After seven years of vacancy, the provincial government, somewhat begrudgingly, declared that they would renovate the building into provincial offices as a way to “regenerate economic growth,” and improve “community spirit” in the neighbourhood.

In the years after the mill’s conversion to provincial offices was completed, federal and municipal authorities joined in on Marysville’s ‘revitalization’ by investing in industrial heritage projects. The federal government, through Parks Canada, formally recognized both the Marysville Cotton Mill and the neighbourhood as historic sites in 1986 and 1993, respectively, and Fredericton’s municipal government began its public history projects in the early 1990s, citing the potential “enhancement of tourism” and increased property value as incentives.

The Marysville historic district, along with the adjacent working-class neighbourhoods, have received significant funding to improve the tourist and recreational appeal; the refurbishment of past industrial rail lines into “linear parks” that cut through the city’s northside working-class neighbourhoods have been touted as a way to compete with the tourist havens of Nova Scotia, PEI and Maine.[3] By following these trails, passersby can access interpretive panels that provide insight into Marysville’s industrial past.

In a fashion similar to the cases of industrial heritage explored by scholars such as Cathy Stanton in The Lowell Experiment, Steven High in Deindustrializing Montreal or in several of Stefan Berger’s works on the Ruhr Valley, Germany, the industrial heritage panels and plaques dotted around Marysville reinforce the social, economic and political hegemony of the Canadian state by providing an uncritical articulation of the past that mitigates conversations surrounding working-class and labour struggles.

Kindred to the signage on the Lachine Canal, a highly prominent Canadian example examined in High’s Deindustrializing Montreal, the interpretative panels and plaques woven through Marysville predominantly focus on the historically distant endeavours of the town’s patriarchal founder and industrial capitalist, Boss Gibson. They also discuss the type of industrial production in the town and the community’s industrial architectural character.

However, like in the cases cited above, Marysville’s heritage plaques and panels pay no heed to the instability caused by the three separate mill closures—in 1954, 1973 and 1975—nor do they make mention of the struggles with anti-unionism, low wages, and difficult working conditions experienced in Marysville. In fact, the municipal plaque dedicated to the mill claims that “the Marysville Cotton Mill flourished until it closed its doors in the 1980s,” and, in doing so, foregoes the historical reality that is the legacy of financial issues and closures that plagued the mill operations.

These recreation spaces and cleansed, aestheticized industrial heritage have become highly attractive to higher-income Frederictonians. In a similar, although microcosmic, fashion to the post-industrial green spaces of New York City’s High Line or Montreal’s Lachine Canal, the Devon-Marysville recreational corridor has become an increasingly gentrified space; craft breweries, high-end coffee shops and luxury apartments and condos have been populating in the area, raising concerns about gentrification in the area.

Beyond the Boss

Dismayed by the heritage projects in Marysville and inspired by Lisa Gasior’s Sounding Griffintown, I initiated an effort to develop a historical audio walk guided by the voices of Marysville residents. With the help of five Marysville residents, my online audio walk “Beyond the Boss: A People’s History of Marysville” steps away from the distant and simplified historical narratives presented in the state-led heritage projects by foregrounding the peripheralized experiences, memories and stories of Marysville residents.

To listen to the audio walk, check out the Beyond the Boss webpage.

[1] Marysville was amalgamated in 1973; Alex Forbes, “A Patriarch’s Company Town: Boss Gibson and the Marysville Legacy,” in Company Houses, Company Towns: Heritage and Conservation (Cape Breton University Press, 2016), 56.

[2] Wilda Pond, Interviewed by Noah Schwarz, 2025

[3] Cathy Jenkins, “Outdoor Recreational Chances Being Ignored,” The Daily Gleaner, April 30, 1991, https://www.newspapers.com/image/1098942032/?match=1&terms=%22Gibson%20trail%22.