By: Sophia Richter

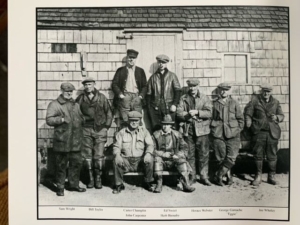

In 1947, the fishermen of Point Judith, Rhode Island, having recently come home from WWII, established the Point Judith Fishermen’s Cooperative Association. It would become an important catalyst for the industrialization of the port’s fishing capacity and by the 1970s was considered to be one of the most successful fishermen’s co-ops in the country. Even so, in 1996 the co-op went bankrupt and drifted into obscurity. Over the course of my oral history work with the Point Judith fishermen of Rhode Island, USA, since 2021, I observed that the closure of their co-op marked a shift in fishermen’s perceptions about the industry. Once the co-op shut down, oral histories revealed the prevailing sense that the industry was “going down the drain”. Fishing families feel this shift in terms of being no longer valued by a society that “just want the sports fishermen and the tourists down there” and is willing to “weed us out [… to] put up condominiums […and] move us up to [a far-away industrial port]”.

My central question was whether these declension narratives were indicative of a wider trend in the economic life and structure of industrial fisheries. Using the co-op’s meeting minutes, newspapers, and oral histories, I was able to trace much of the wider industrial fisheries markets and politics to see how it actually compared to wider trends in fisheries and industrial history. While fisheries have not found solid ground in the field of deindustrialization, this project was an effort to make these linkages.

Up until the 1970’s the majority of fishing capacity that took place off the coast of New England were from British, Polish, Norwegian, and Soviet fleets. Trade liberalism kept domestic fleets from modernizing. By this point, global momentum, beginning in Latin America, to extend nation-states’ jurisdiction 200-miles from the shore, catalyzed American fishermen to call for nationalization as well. In 1976, Congress extended U.S. jurisdiction from 12 to 200 miles. This act of Congress went directly counter to then-president Jimmy Carter’s platform on free trade. In this light, Carter mandated that fishing rights be traded away if not “fully utilized” by domestic fleets. In response, Congress passed the American Fisheries Promotion Act of 1980 and the Commercial Fishing Industry Anti-Reflagging Act of 1988 to modernize the fleet. Not only would this trigger an era of economic nationalism, but it would result in privatization. While the federal government offered vessel-improvement loans, private banks and insurance companies flocked to the industry at unprecedented rates. Additionally, in their effort to regain access, foreign fishing firms began investing in domestic fleets and processing plants.

The first technical report on the topic was completed by the United States General Accounting Office (GAO) in 1981 to investigate “foreign investment in the U.S. seafood processing industry”.[1] While “Americanization laws” were meant to curb foreign ownership, others, such as Jeremiah J. Sullivan, an American professor of international business, argued that “such vast sums will be required” to modernize the American fleets “that foreign capital will be needed” and that “growth is the goal of everyone”.[2] By this point, it was clear that the fishing industry was experiencing “an overcapitalization problem” and that foreign investment was enabling an ever-expanding capacity within fisheries that were crippling under their pressure.

Despite two decades of “Americanization” of the fishing industry, New England fisheries anthropologist reported that in 2001 “the involvement of foreign investors in local seafood processing is a pattern that is being repeated in many ports” and processing foreign fish products is an important aspect of New England’s processors. The Point Judith co-op ultimately shut down because of these shifting patterns of capital. Its records suggest that this global financialization of the industry made it a precarious endeavor to continue relying on the localized and limited cash-flow of the cooperative model. Not only did it look for buy-outs from Spanish, Japanese, and Peruvian firms, but it sought out another type of finance capital: private equity. Before any of this could be established, though, the co-op went bankrupt.

Private equity has since found strong roots in the American fishing industry. In 2015, a fish firm, Blue Harvest, was launched. It was a vertically-integrated company and the single-largest permit-holder for groundfish in New England, owning a quarter of all the groundfish vessels fishing out of the port. Tracing its ownership back, ProPublica pointed to a Dutch billionaire family who owns private equity firm as well as other commodities and renewable and fossil fuel ventures from New Bedford to Bangladesh.[3] Private equity is most often used to consolidate an industry before reselling it at a massive profit. Because of this model, it favors speculation over sustaining an industry for the long-term. The report additional uncovered links between private equity ownership and exploitative fishing labor conditions. In the summer of 2023, Blue Harvest filed for bankruptcy. Not long after, Massachusetts legislators wrote a letter demanding “transparency” in the bankruptcy proceedings and accused the owners of the company of asset stripping, failing to pay “over $100 million in debts and harming countless small businesses in the New Bedford area”.[4] “Americanization” was undermined by financialization and the closure of the co-op was a signal to this shift.

In conclusion, studying decline in fisheries offers a few lines of inquiry for deindustrialization. In a way, the co-op was an example of social reproduction with the industry and was a generative site for analysis. Secondly, financialization within the fishing industry was a significant process that contributed to industrial decline. While there is a general lack of data on the topic, the globalized and speculative mechanisms by which capital moved within fisheries provided an important framework for understanding fishermen’s experiences. In this light, it was valuable to consider sites of decline, even if they didn’t lead to closure. Lastly, just as deindustrialization studies has interrogated the politics of closure, there is value is examining the politics of “boom-and-bust”. The “growth paradigm” underpins the wider structures of capitalism, and thus deindustrialization itself. Decline in fisheries demands an approach that denaturalizes this paradigm.

[1] General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Les AuCoin House of Representatives, CED-81-65 (1981).

[2]Jeremiah Sullivan, Foreign Investment in the U.S. Fishing Industry” (Lexington, Massachusetts) 1979: 2, 163.

[3]Will Sennott, “How Foreign Private Equity Hooked New England’s Fishing Industry”, ProPublica, July 6, 2022.

[4]Will Sennott, “Warren, Markey and Keating demand answers from Blue Harvest owners”, The New Bedford Light, February 13, 2024.