The processes of deindustrialization not only change the economies and visual landscapes of former industrial areas but also affect – often negatively – the everyday lives of residents in those areas. Deindustrialization often eventually leads to gentrification and displacement of low-income residents, weakening social ties within communities and challenging working-class identities.

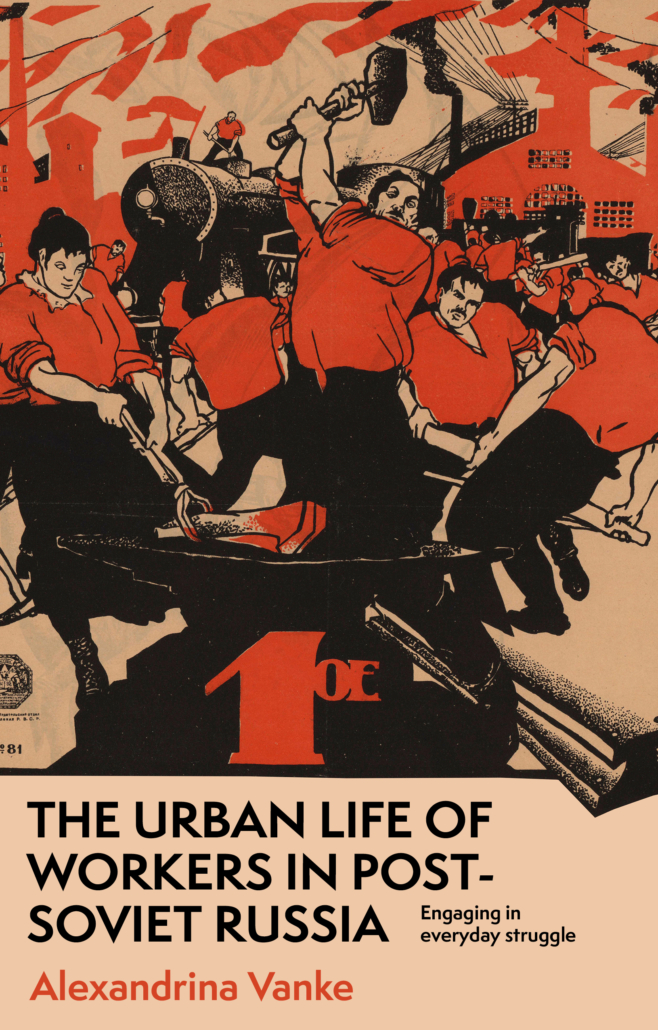

A global phenomenon, deindustrialization nonetheless has a local dimension (Mah, 2012). Post-industrial changes may manifest themselves in particular ways in different countries depending on their political regimes, economic models and social welfare systems. That is why it is important to study deindustrialization in multiple locations and pay attention to how it influences the quality of life of working-class people and other disadvantaged social groups. My new book The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia: Engaging in everyday struggle creatively explores the lived experiences of deindustrializing communities in two major post-industrial cities of Russia, namely Moscow and Yekaterinburg. Drawing on multi-sited ethnographic research, I argue that workers and ‘ordinary people’ are actively engaged in everyday struggle.

By this, I mean the creative forms of resistance to the destruction of Soviet-era industrial infrastructure through its collective maintenance, participation in informal economic activities (see also: Morris, 2016), and peaceful resistance to both neoliberalism and neo-authoritarianism (intensified in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war). I explain the engagement of workers in mundane resistance due to restrictions on open collective protests in contemporary Russia.

Understanding deindustrialization with structures of feeling

In the book, I explore the lived experiences of deindustrializing communities using the concept of “structure of feeling” introduced by sociologist Raymond Williams who viewed it as ‘the living experience of the time’ (Williams and Orrom, 1954: 21) and ‘the spirit of the age’ (Williams, 1967: 11, 363). Drawing on my ethnography of Russia’s industrial neighbourhoods, I suggest that the structure of feeling is as an affective principle regulating senses, imaginaries and practical activities of local communities within socio-material infrastructures.

However, I find Williams’s distinction between ‘residual’ and ‘emergent’ cultural forms helpful for the study of deindustrialization, enabling us to distinguish between residual and emergent structures of feeling related to industrial and post-industrial modes framing everydayness in deindustrializing areas. According to Tim Strangleman (2017), ‘an industrial residual structure of feeling’ allows a better understanding of post-industrial change in contemporary societies. Strangleman (ibid) also points out that residual structures are often resistant.

In the case of Russia, the Soviet industrial legacy continues informing the sensual experiences and spatial imaginaries of long-standing residents of industrial neighbourhoods with mixed social compositions. Convergences (and sometimes tensions) between Soviet and post-Soviet structures shape social relations between differentiated residential groups bearing particular values and influence on how they sense and imagine their neighbourhoods.

Long-standing residents, including workers and some professionals, tend to bear values of commonality, mutual support and shared space informed by the residual Soviet-socialist structure. New residents belonging to the educated middle classes tend to bear values of individuality, private space and consumption informed by the emergent post-Soviet-neoliberal structure.

Reflecting on intersectional inequalities in the study of deindustrialization

It is important to take into account inequalities when we study deindustrialization in multiple locations to reflect on unequal distribution of resources and power imbalances. One chapter of The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia considers intersectional inequalities visible in the space of two industrial neighbourhoods that I studied. My ethnography of deindustrializing communities develops Pierre Bourdieu’s (1984) idea of objectification of social divisions in physical space and Doreen Massey’s (1991) understanding of a sense of place emerging from unequal distribution of power.

In the book, I explain that working-class men and women, as well as migrant workers and working-class pensioners, tend to spend time in particular places inside their neighbourhoods. This partly helps them to form their gendered sense of place. For example, such places, as garages, small workshops and even benches near social housing blocks, accommodate particular practical activities that bear some markers of class, gender, ethnicity and age. These places create the opportunities for cultivating a sense of belonging to local community.

At the same time, both neighbourhoods are experiencing gentrification, leading to new places for middle-class residents squeezing out working-class people from public places.

Apart from this, working-class people face problems of reduced social welfare support and a lack of jobs suitable for them in both study areas due to deindustrialization. This prompts them to find alternative ways to overcome difficulties, such as relying on their networks of solidarity and launching independent small businesses that are still divided into feminine and masculine professional activities.

What about international similarities?

Despite differences in economic and political orders in Russia and other countries, working-class communities experience similar problems, including worsening of living conditions, displacement from deindustrializing areas and the silencing of their experiences. My research brings particular attention to the ways that working-class people counteract job loss, economic hardship and neoliberal neo-authoritarianism. Such examples of workers’ everyday struggle can not only be found in Russia but also in other parts of the world.

You can learn more about the role and place of working-class communities in contemporary Russian society in my new book. Please find it at your university or local library or purchase it on the website of Manchester University Press.