Coking plant Zollverein (1961 – 1993) in Essen, western section of the UNESCO World Heritage site of the colliery Zollverein (1847 – 1986). February 2024.

Ute Eickelkamp, senior Research Fellowbat the Institute for Social Movements at Ruhr University Bochum, and Stefan Berger, Professor of Social History and Director of the Institute for Social Movements at Ruhr-Universitaet Bochum

This month’s blog is in two parts, read the second part here

As deindustrialization changes life-worlds and landscapes, it transforms public places and spaces, and even creates new ones. Who identifies, designs, appropriates and uses public space is of deep concern for the wellbeing of civil society and democracy. And yet, historical scholarship of “the public” is a late arrival in Germany. Against this background, we hone in on the perspectives and practices of living in public that people who see themselves as “working class folk” have forged in Germany’s former heartland of heavy industries, the Ruhr Valley. We are especially interested in people’s notions of “time out” and “out-in-nature” frames in and outside dedicated spaces. We distinguish between people’s use of “green” spaces created as such for them, such as the old park or the new promenade along the restored river, and those green and blue places they have made and culturally own – by way of working and socialising in their allotment garden, fishing in the canal, or “hanging out” around a track in the forest.

Well before the last out of hundreds of black coal mines closed in 2018, a thriving heritage movement has turned the Ruhr’s former industrial sites into public space. Former collieries, cokeries, steel mills, ironworks and breweries now host industrial history museums, art studios and galleries, theatres, as well as new green industries. A substantial section of former places and infrastructures of heavy industries have been returned to “nature” – and, therewith, to “the” people, either permanently through the rewilding of brownfields, or temporarily through the concept of “nature-for-a-while/Natur auf Zeit, which allows land to be reused for commercial and industrial purposes. The functional and legal change from closed industrial area to green, educational, leisure, or entertainment space open to the general public expands the scope for participation in the transformation of the Ruhr society and ecology into a climate-adjusted region. But it also takes away places people have made their own all along. Certain questions flow from this: How have ideas of leisure enjoyed in the outdoors changed in the process of structural change – the deindustrialization and neoindustrialization of a region within a landscape park? And can green spaces ever be “class-neutral”? We tackle these questions by visiting some such places and spaces of socio-material transformation of the “common folk”.

“Wow, it is so green here!,” is an exclamation often heard in the contemporary Ruhr from outside visitors still expecting to find the polluting industries, especially coal, steel and the chemicals’ industries. People who visit the Ruhr from the outside, be it from other parts of Germany or from abroad, expect a grey industrial moloch, one in which the soot still collects on window sills and the washing is grey and black when it is collected from an outside washing line. Why does the image of the Ruhr lag behind its reality? There are many reasons for this, including a lack of familiarity by the rest of Germany with the Ruhr area, which has certainly not been a tourist destination during the high point of industrial production in the 1950s. However, things are changing: millions now visit the Ruhr and they are, by and large, attracted by the icons of industry formed into industrial heritage – the mines and steelworks that once made this region into the key industrial heartland of Germany.

The vast industrial heritage landscape awaiting the visitor to the Ruhr spread out before them in literally dozens of sites extends across 700 kilometres of cycling routes that were once railway tracks to transport the “black gold” and the steel products “made in Germany”. This celebration of industrial heritage, which has its origins in a double triumph narrative –that of successful industrialization and that of successful deindustrialization – has also led to the celebration of “industrial nature” (Industrienatur). The narrative on industrial nature starts from the admission that industrialization led to terrible forms of destruction of the natural environment but it goes on to say that the lesson has been learnt in the Ruhr: the search for more sustainable economic growth of cleaner industries that live in harmony with nature has led to a return of nature in more splendid and diverse forms than it ever was before industrialization. Whilst some of this is tantamount to “greenwashing”, e.g., the Ruhr still has some of the most polluting coal-fired power stations in the whole of Europe, there is undoubtedly also an impressive balance sheet when it comes to “renaturing the Ruhr”.

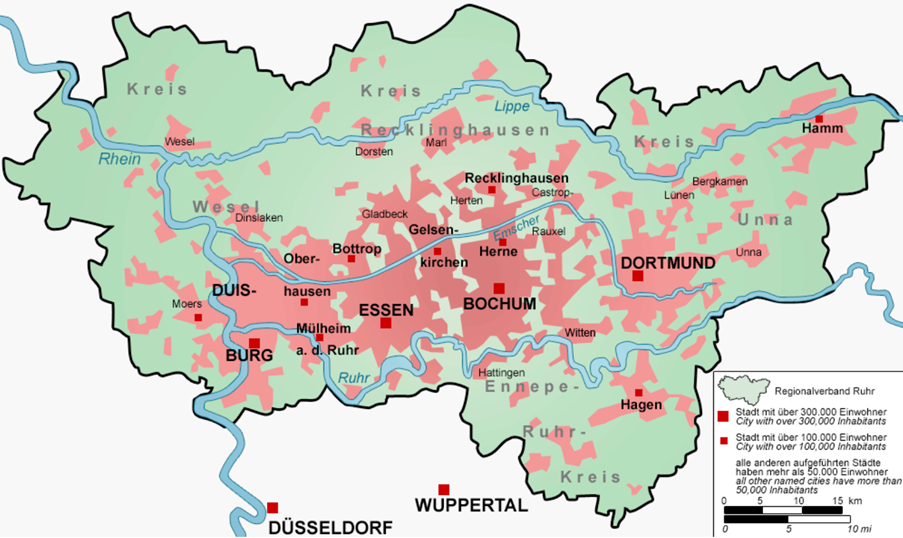

Arguably the most impressive project here is the restoration of the Emscher river which cost billions of Euros, financed by local, regional, national and European funds. It led to the creation of a massive landscape park stretching from Dortmund in the east of the Ruhr, where the Emscher river originates, to Duisburg in the west of the Ruhr, where the Emscher river joins the Rhine. It has turned the Emscher from one of the most polluted rivers in Europe – a cloaca maxima – into one of its cleanest, in the process putting all the waste underground and cleaning it in brand-new, state-of-the-arts water treatment plants. Overseen by the Emschergenossenschaft Lippeverband (EGLV), it is a project that has attracted attention across Europe and around the world. It promises a “green-blue” future to the residents living near the new Emscher while promoting cooperative forms of citizen participation in shaping the way in which this spectacular ecological remediation process is going to look.

But how do the people who live in the cities and towns alongside the river react to this transformation? Many industrial sites were located along the open sewer receiving their waste, while the Rhine-Herne canal, a federal waterway used for shipping coal and steel, runs parallel to the Emscher. Thus, many of the communities living closest to these industrialised waterways traditionally had a strong working-class composition, with middle-class elements being rather rare. Proletarian milieus and cultures dominated the geographical scene through which the canalized Emscher went. How did those people and those communities react to the massive transformation right in front of their doorstep, which was certainly not of their own making, even if the EGLV has for some time now sought to engage these communities more in the transformation of the Emscher and its riverine landscape?

Our research has addressed these issues and we found that the people we got to know and spoke with over two years in three working-class districts of Recklinghausen almost unanimously appreciate the Emscher conversion. Men and women of different generations and cultural background, among them retired coal miners, metal and steel workers, chemical factory workers, their wives, as well as truck drivers, shop assistants, and other precariously employed or unemployed people, told us, „Das haben sie schön gemacht” – they did a great job”. Everyone remembers the horrible stench of the Emscher as open sewer, its toxic sludge in which people had drowned, their cellars being flooded with wastewater as much as other impositions of “locally typical” (ortsübliche) levels of pollution. When Eickelkamp’s grandfather, a local miner, was able to build a small house on cheap land by the Emscher, his wife cried for months before she got used to the smell and social marginality of “living by the water” then. A subsistence garden and a slowly growing neighbourhood offered some relief.

Today, farms, residential homes, commercial premises and “nature” vie for space near the “Emscher Promenade”. The gates to the former operating route of the water manager to access the steep banks of the open sewer have long been opened to cyclists, dog walkers and flaneurs, and the promenade hosts a permanent open air art gallery and “experience sites” inviting people to behold, smell, and even touch the water teeming with life. A new river sensorium has arrived.

Undoubtedly, the reconstruction of a river and its surrounds along 83 kilometres through a densely populated, polycentric urbanity requires the orchestrated planning of many actors. Yet those especially older interlocutors who regard themselves as having contributed to the making and remaking (post WW2) of the Ruhr region clearly are not makers in this restoration project of late. “They” did a great job for “us” to enjoy reflects a positionality as receivers of the good. And one conversation in particular suggests that not everyone is happy with this perceived allocation of roles. A group of men who regularly meet for Sunday drinks – an electrician, a former underground metal worker, and a butcher – acknowledged that the Emscher conversion is the “best project for the northern Ruhr since World War 2”, a “right step into the future”, and a process of farewelling the open sewer that will provoke the development of an “Emscher nostalgia” in a decade or so when people will remember in a “Heimat-engendering” manner the old “poo canal“. But these men also shared that they harbored ideas for an Emscher culture, which is to be realized independently from the municipality, the EGLV, Regional Association Ruhr, and other protagonists of the green transition. Like several unemployed men who meet up at the cross-roads of bicycle tracks near the river, one man, an electrician in his mid-thirties, deemed the restoration of the Emscher landscape as wasteful. Noting that, in some places, there was already nature where nature restoration is taking place, and wondering why he would need a viewing platform to look onto trees, he judged: “Unsere Arbeit zählt weniger als die Natur” (our work counts less than nature).

Perhaps the key question for “players” big and small in the field of greener and bluer future making is how the growing population living precariously in the former industrial working-class districts (where unemployment rates reach up to 16 per cent) will participate in the fourth (industrial) nature of the Ruhr. A glance at past and present proletarian practices of “owning” green space might bear some clues.

“In the summer, my mother would walk with us kids from Hochlarmark all the way to the Rhine-Herne-Canal for a swim”, a former coal miner in his eighties told us in his allotment garden. To this day, swimming in this federal waterway is illegal, and yet people of all ages do so while the water police tends to look away. Jumping off bridges or hanging onto shipping barges have long been part of the (male) youth culture, while old men sit on the bank to fish and families cycle to a favorite picnic spot. A hobby fisherman exclaimed that the litter the weekend folk leaves behind was appalling, and that he and his mates have privately organized regular clean ups of their “beautiful canal”. In their documentary film of the Emscher conversion, Emscher Skizzen, Christoph Hübner and Gabriele Voss show a middle-aged woman, her husband and their dog sitting on a blanket in the sun by the canal at a place nicknamed “Schweinebucht” (pig’s bay) in the Ruhr’s poorest of cities, the once wealthy coal town of Gelsenkirchen. The woman offers the camera a lengthy and moving reflection on the change of values, from a shared sociality, care for others and a kind of working-class egalitarianism, to a competitive, individualized, jealous and aspirational mindset and behaviour, including in the sphere of leisure. Socially speaking, the past is remembered as being better than the present – which is still the case today. A recent, much-liked Facebook post about Gelsenkirchen makes this clear, in which men and women remember the “golden” 1980s and 1990s at the Schweinebucht. Crucially, the post demonstrates how people have appropriated the place by making it a tradition of being “out in nature” here.

Facebook post accessed 4 June 2025.

What then, do such stories tell us? Our perception is that, more than ecological targets in and of themselves, two things especially are important for the working-class people who “made” the Ruhr region and who have lived its structural transformation: the social productivity of nature in the sense of being a lively and affordable outdoor setting for spending time together, and the feeling of being at home (in the sense of a domestic intimacy) that such socialising with familiar others in “nature” engenders. If the construction of extensive and networked landscape parks on former industrial sites and the renaturalization of the Ruhr’s central river are very well received, the “designer environment” also correlates with and indeed encourages individualized leisure activities, such as flaneuring or cycling in a postindustrial public that has lost much of the improvisational, home-made and enlarged domesticity of old. For better or worse, the sites of labour and the lifeways of working-class folk, many of whose families had migrated here from different parts of Germany, Europe and beyond, have become a tourist attraction for visitors from afar. Meanwhile, people at home in the Ruhr are in the midst of forging their own cultural heritage of being in the outdoors, a process that shows cracks and contradictions in the ways nature is valued and, by extension, in the socio-material transformation of the region at large.