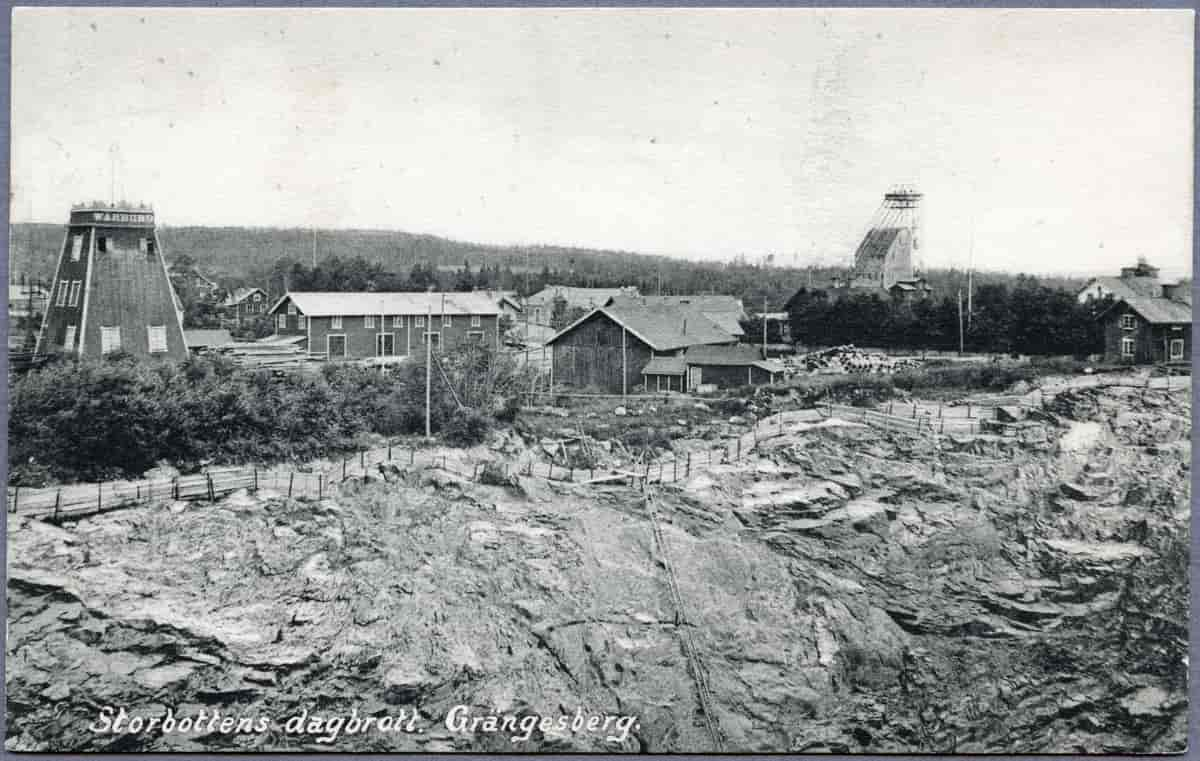

Photo: Swedish mining community of Grängesberg in Bergslagen, circa 1910. Source: Store Norske Leksikon

Northern Sweden is facing a high-profile industrial transformation with major investments in the name of climate change. Battery factories and new ‘green steel’ mills are held up as major industrial transformations both by the companies themselves and by the mainstream media. However, the steel industry is far from environmentally friendly, being a resource and energy-intensive polluter with extensive impacts on water, soil, and air. Not to mention the historically harsh employment conditions and harmful working environments. In this context, many stakeholders are now promoting a new narrative of fossil-free steel production as the basis of a new “green” industrial revolution, offering a just transition in the form of re-industrialization.

In the northern region of Norrland, which is the geographic size of the UK, industrial investments are now expected to fundamentally change some local communities. However unrealistically, estimates suggest 100 000 new residents will be needed. With these relatively well-paid industrial jobs in newly built factories, other parts of the region are likely to be drained of labour and working-age people. In addition, there is a ‘fly in fly out’ scenario where jobs are created but communities still fall behind in terms of infrastructure, public services, and other necessities of life. Green steel production requires an enormous amount of electricity. It is not clear where it will come from or what it means for other consumers and the price of energy, nor do we know if steel production lines elsewhere in the country will have to be shut down as a result. Simultaneous industrialization and deindustrialization in the same region have been the hallmark of the Swedish experience.

Currently, I am involved in a research project that examines how hopes and concerns about this expected industrial transformation are articulated and affected by previous industrial transformations, such as deindustrialization. The study will be implemented through a combination of historical and contemporary case studies of the steel industry in Sweden and the UK. The historical approach addresses the legacy of industrial change, which means understanding the place-based legacy of deindustrialization and how local and translocal factors affect communities and working life in a broad sense. A first study has been launched in an industrial community of about 10 000.

The project’s geographical starting point is not Norrland but Bergslagen, an old industrial region in the middle of Sweden that has undergone a significant industrial transformation. Once considered the heart of Swedish industry, Bergslagen’s past has been mystified and almost mythologised as the cradle of Swedish industrial society. When Bergslagen was at its peak in the 19th-century, Norrland was ‘the land of the future.‘ Rich in natural resources Norrland became an object of the exoticism of the north. The north was slowly colonized by the south over the 20th century. Post-war labour market initiatives, which were part of the Swedish model, encouraged southward migration and thus reinforced inter-regional exploitation within the country’s borders. The migrant workforce to Bergslagen’s industrial communities in the mid-20th century often came from Norrland and from culturally and geographically close areas of Finland.

The steel slump in the 1970s triggered a process of de-industrialization. Closures, downsizing, and rationalization, lead to the impoverishment of industrial communities with no prospects for future regrowth. In the 1980s, Bergslagen and Norrland were seen as the two most depressed areas in Sweden and in dire need of regional policy intervention. Bergslagen has probably been seen as the most hopeless case with a decentralized special steel industry that survived in some places, although the number of employees and local inhabitants has relentlessly declined. In others, post-industrial dreams of tourism and culture have patched up the deep wounds of de-industrialization.

The aboriginal people of the North, the Sami, were not included in either the hopes for the future or the out-migration narrative. Objections to land use, such as mining and infrastructure constructions, have always existed, albeit in different tone. One of the world’s largest underground iron ore mines has been present in Norrland all along and large parts of the coastal area have remained heavily industrialized based on commodity industries such as forestry, iron and steel. Recently, this has become more pronounced with reference to Sami rights under threat to livelihoods and entire cultures. Growth and expansion do not always lead to societal improvements.

The new narrative of industrialization is more conflicted than before, shaped by the scars of history and the fear of future ecological collapse.

To participate as a historian in a project that explicitly deals with the consequences in the future feels a bit unusual. Despite its palpable despair, the empirical space of deindustrialization studies feels more at ease, even if it is about closures and demographic decline, community devastations and abandonments, individual and collective depressions, outmigration, and profound identity crises. But it’s also about the pride and dignity of residents, an indomitable will to stay despite logistical difficulties and welfare restrictions. All this with immediate and long-term consequences is nevertheless part of the historically trodden landscape. In the overall approach of the project, hopefully, there will be a space carved out to better understand how memories and experiences of deindustrialization and its specific trajectories influence perspectives on the green transition. Just like industrialization and de-industrialization, deep decarbonisation of extractive and foundational industries will involve widespread social and economic change, somehow.

Tenby, South Wales. Wikicommons. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Tenby, South Wales. Wikicommons. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.