Keith Gildart is Professor of Labour and Social History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. He is currently working on a book (with Andrew Perchard) on popular music and deindustrialisation in the Britain and the United States.

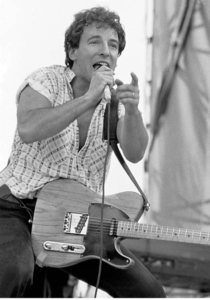

In November 2025, the BBC invited me to take part in the making of a documentary on the impact of Bruce Springsteen’s music on working class industrial communities. The filming took place in the former coalfields of North-East England that have long been ravaged by the impact of mine closures, unemployment, poverty, inequality, and depopulation. Both the villages of Easington and Horden retain the footprints of the coal industry in buildings, commemorations, and the physical and mental scars carried by former miners and their families. Walking through their streets my journey was soundtracked by songs that illustrated the rise and fall of coal and the fear of ‘dole’ (unemployment).

In 1985, Springsteen performed at St James’ Park, Newcastle, devoting some of the proceeds from the concert to the Northumberland and Durham Miners Support Group. Songs performed at the show included ‘Johnny 99’, ‘My Hometown’ and ‘The River’, each of these speaking to the experience of industrial work, plant closure, and pride in a sense of place and identity. The power and delivery of these songs resonated with miners who attended Springsteen concerts in Newcastle, London and Leeds that came three months after the defeat of the National Union of Mineworkers in the strike of 1984/5. Springsteen was the latest songwriter who sought to communicate with English working class in a crucial decade that would see the beginning of the end of the coal industry and attack dilution of trade culture, activism, and power.

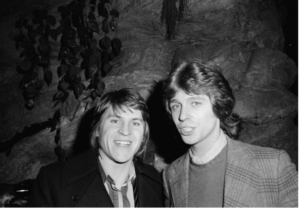

The protracted process of deindustrialisation and the British musicians who had captured aspects of the changing nature of working-class has yet to fully captured and explored in the academic literature. Both Alan Price and Georgie Fame were musicians who grew up in towns that were steeped in the history of coal and industrialisation. Price’s Washington (County Durham) and Fame’s Leigh (Greater Manchester) were part of the larger coalfields of the North East and North West England. Deindustrialisation in both coalfields was already underway in the 1960s and exacerbated by the massive closure programme introduced by the Labour Government between 1966-1970. Price found initial success through his membership of The Animals and popularity on both sides of the Atlantic, while Fame was instrumental in the burgeoning mod scene of the 1960s, his residency with the Blue Flames at the Flamingo Club, and as a key figure in the British beat boom.

In 1971, Price and Fame released ‘The Dole Song’, which marked the beginning Price’s foray into charting the rise and fall of the Durham miners. One protagonist in the song had lost his sole down a hole and was now marooned between various other jobs. Three years later, Price recorded sessions for two albums ‘Saveloy Dip’ and ‘Between Today and Yesterday’. These provided both historical and autobiographical insights into coalfield life. Characters here include ‘Willie the Queen’ a kind of working-class northern version of the Kinks ‘Lola’, and ‘Poor Jimmy’ the miner turned boxer.

The past and present of the Durham coalfield collide in Price’s ‘Jarrow Song’. This was released in 1974 when the miners had won their second victory in two years in a national strike over pay. However, mine closures and the destruction of community was also a factor in rising militancy in the coalfields. The mobilisation of the ‘geordie boys’ in the Jarrow March of 1936 against unemployment was repackaged in a popular song that spoke to the working class struggles of 1974. In contrast to Price, Fame did not lyrically engage with his childhood in a coal mining town. Yet the cover of his 1971 album ‘Going Home’ presents a black and white image of the South Wales mining village of Tonypandy. This had been the scene of clashes between striking miners and police/military in the 1910-11 coal dispute.

Both Price and Fame were early chroniclers of the devastating impact of deindustrialisation of the English coal towns in the 1970s. In a fleeting period between 1974 and 1979 a long-term future for the coal industry was envisaged along with a halt to mine closures. Such optimism was soon dashed by the election of the Conservatives. This led to further interventions by musicians in both documenting and critiquing the process and impact of deindustrialization. In 1981, the Specials released ‘Ghost Town’, a year later Elvis Costello wrote ‘Shipbuilding’ and in 1984/5 both Billy Bragg and Paul Weller penned songs lamenting the closure of coal mines and weakening of trade unions. These were complemented by songs referencing the industry by Mark Knopfler, and Sting (also from the North East).

The 1980s have provided scholars with a key decade in which to explore the soundtrack of deindustrialisation. Yet there is a longer history here, and Price and Fame are just two examples of musicians who were already grappling with a world that had been turned upside down by the closures of mines, factories, and shipyards in the 1960s.

In 2024, Bruce Springsteen returned to North East England and performed in front of a huge crowd at the Stadium of Light in Sunderland. The Stadium had been erected in 1997 on the site of Wearmouth Colliery that had closed in 1993. Springsteen had supported the miners in 1984/5 in their fight to keep the mine open but now the industry had long disappeared from the topography of England. The music of deindustrialisation, the sentiments of Springsteen, and the giant miners’ lamp outside of the stadium remain as reminders of the link between work, culture community and the lost worlds of industrial Britain.

The songs of Alan Price and Georgie Fame are available on CD and streaming platforms. The documentary on Springsteen and Britain will be broadcast on the BBC in Summer 2025.